Revisiting China

The Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni accepted an invitation by Mao Zedong’s government to visit China in 1972, during the height of the Cultural Revolution (1966 – 1976). His assignment was to make a film documenting the achievements of Communist era China. Throughout his visit which included a trip by train from Hong Kong to Beijing, he was accompanied by Chinese minders. The result was Chung Kuo: Cina, a fascinating documentary in which Antonioni just let his camera roll. In Marvelous Possessions: The Wonder of the New World, the literary historian Stephen Greenblatt attributed the concept of wonder to a displayed object’s power to “stop the viewer in his or her tracks, to convey an arresting sense of uniqueness, to evoke an exalted attention.” For Antonioni, China was that displayed object. At the time, China was closeted from the world and the country held a deep fascination for many in the West, particularly among intellectuals and artists. Antonioni was so enthralled by China that all he could do was to film anything and everything, particularly the activities of ordinary people going about their daily lives. To the Chinese government, Chung Kuo: Cina was deemed an ill-fated project and immediately banned. After forty years, the ban was lifted . The hosts were confounded by Antonioni’s interest in capturing the banalities of life, rather than to showcase the epic story of Communist achievements. They were confounded by the lack of narrative structure in favor of extended observational takes, but this was in keeping with Antonioni’s reputation as a cineaste of emotional displacements and indeterminate expressive moods. They could not understand why he could not play by the rules expected of him and supplied to him by his guides as he traveled in and around Beijing, the Yangtze river and Shanghai. Chung Kuo: Cina, is a film full of languorous and enchanted takes on quotidian Chinese life, the true subject of which is Antonioni’s unmitigated mesmerization of what he experienced in China.

In 1984, my initial experience of China was similarly intoxicating and I feel extremely fortunate to have been able to be there at the tail end of an old China that was only being to transform into what it is today, full of skyscrapers, speed trains and freeways. I often recall that visit as a kind of placeholder in time for me. I was just getting started in my life as an artist. The year 1984 marked barely three and a half years after the formal establishment of special economic zones (SEZ) that exempted four southern cities from the planned economy system as authorized by the Chinese central government in Beijing and five years prior to the 1989 student led Tiananmen Square protests that would be violently quelled by the government. Following from paramount leader Deng Xiaoping’s concept of The Four Modernizations program of revitalizing China’s deficient defense, agricultural, industrial, and technological sectors, the SEZs were concentrated in Guangdong and Fujian provinces, with three of the SEZs located in the Pearl River Delta, close in proximity to Hong Kong. Located between Hong Kong to the south and Guangzhou, the premier city and capital of Guangdong, to the north, Shenzhen was designated as the first SEZ in late 1979. A former county township with a population in 1979 (with just 30,000 people living in the urbanized area), today’s Shenzhen is a metropolis of 14 million.

The purpose of my visit to Guangzhou in 1984 was to find my family roots. I had an exhibition at the Miyagi Museum of Art in Sendai, Japan, and so I decided to add a visit to Hong Kong and mainland China. I had relatives in both Hong Kong and Guangzhou. My mother, who had been ailing for several years, urged me to pay a side visit to the family in Hong Kong and to our ancestral home in Guangzhou. The memories that I carry from that trip remain vigorous and represent an important turning point in my life.

I flew from Tokyo and stayed several days in Hong Kong where I secured a two-day visa to visit mainland China. I passed through Chinese customs from Hong Kong’s Northern Territories border. There were two long queues, one for foreigners and the other for non-China resident Chinese. Despite my Canadian passport, I was placed in the latter queue. Behind the customs gate, I could see a large metal fence and what seemed like hundreds of ungroomed faces poking through the openings. Once into China, I was immediately confronted by numerous currency sellers. At the time, China had a two-currency system, one for foreigners and one for domestic users. The foreign designated Chinese currency was worth a lot more as it was exchangeable for other world currencies while the domestic one could only be applied within China. Conversely, it would be far less expensive for a foreigner to use domestic use currency to make transactions despite that the numeric value for both currencies were supposed to be identical. I would soon learn that many of the currency sellers were Chinese agents whose goal was to illegally entrap foreigners to exchange their hard currency for domestic use currency.

Somehow amidst this crowded entrance to China, my mother’s cousin, Lum Fook, recognized me. There are Lums on both sides of my family. Lum Fook was dressed in a slightly tattered Mao suit, much like everyone else around him. We stepped onto a train; the engine festooned with colourful political flags. The dated-looking train would soon depart and young women in what looked like military uniforms stood at attention with one arm in salute. The Chinese anthem came on over speakers, a signal for the train to leave the station.

On the train, the scene was cacophonous. I could see a man carrying a small pig in his arms while others carried new electronic goods, mostly small television sets, still in their boxes. The train was old but clearly so were the tracks as the cars swayed side to side and up and down. Despite this, two vats, one of stewed chicken legs and the other of white rice, were trolleyed down the aisle, kept hot by gas burners. It looked dangerous to me, an accident waiting to happen. The entire car smelled of rice and chicken. Raunchy middle-aged men, all visiting from the Chinese diaspora or Hong Kong, shouted out peccadillos to the young female server, who, unfazed, would catapult bits of chicken stew off her ladle at the most flamboyant offenders. The men appeared to take it as a badge of honour to have droppings of stew mark their clothing or countenances.

I stayed at an old communist era hotel that today no longer exists. My room afforded an extraordinary view of a large iron bridge over the Pearl River. Lum Fook marvelled at the room: he had never before been in a hotel room, nor had he ever seen the river from this vantage point. I offered him the complimentary toiletries, which he gladly pocketed. I assured him that I would be fine on my own for the day and that I looked forward to meeting him again and his family for dinner.

After a brief rest, I exited my room and a female floor attendant appeared almost as though out of nowhere. She greeted me and then walked with me to the elevators. A slight man in a black Mao uniform with downcast eyes entered the elevator with me. I would soon discover that he was my unofficial minder, following me everywhere from the time I left my hotel room to when I retired to my room for the night. I would walk into various stores and he would follow at some proximate distance. I would enter a restaurant and he would lounge about outside until I completed my meal.

Sometime later I met Lum Fook again in the hotel lobby. He suggested a walk to nearby Shamian Island, an important site for foreign trade from the Song (960-1279) to Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). During the Qing Dynasty in the 19th century, it became part of the French and British concessions. Shamian Island played an important role during the sordid history of the Opium Wars and it still retains many colonial mansions built by the Europeans. Later we visited the newly opened White Swan Hotel, one of the first so-called western-style luxury hotels to be built in China. The hotel is still there today. Opened on the southern side of Shamian in 1983, it could only be reached via a 600-meter-long private causeway. I remember travelling by taxi over marshland to reach it. The hotel lobby had a field-mice problem and workers in smart uniforms could be seen swatting at them with traditional Chinese whisk brooms. There was a bowling alley in the hotel, and I saw young and hip Guangzhouers try their hands at bowling, many of them tossing the balls with both hands, causing evident dimpling of the lanes. There was a coffee shop as well, but I soon discovered coffee meant instant Nescafé. Lum Fook had never had coffee before and did not like the taste at all. Neither did I but for different reasons. All of the servers wore name badges with English first names. Before we were finished our cups, a waitress came by asking for payment. I remember well what she said in heavily accented English: “Please pay now. American-style.”

The old core of the city that aligns closely to Shamian, including the Chen Clan Ancestral Hall, the Temple of the Six Banyan Trees, a Buddhist temple and pagoda complex first built in 510 CE, the Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hall, the People’s Park, which was established as the first public park in the city in 1921, and the Yuexiu Park with its famous sculpture of Five Rams, a symbol of Guangzhou’s mythical roots as born from five rams, were at the time of my first visit the main areas of touristic and even civic circulation. Since then, the entire central city district has shifted eastward and the city as a whole has become unrecognizable.

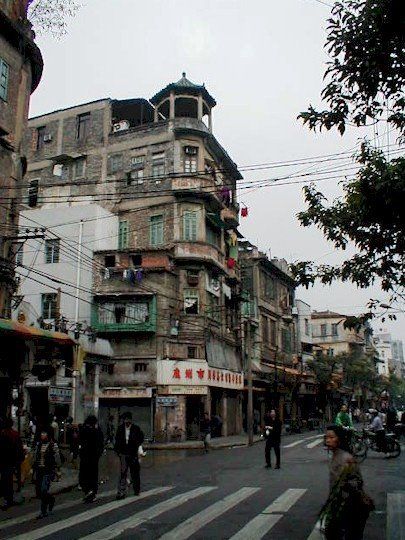

Much of Guangzhou in 1984 was defined by three-level building complexes with inner courtyards that served as the common area for the neighbouring residences. The main streets had a kind of ramshackle but bustling look, not dissimilar to what I would later discover in Havana, Lima, Dakar, Delhi and even Tuanlicun on the outskirts of Beijing many years later. Buildings on main streets were built to the edge of the street with the ground floor indented to accommodate arcaded sidewalks. The streets themselves were often a mixture of indifferently patched asphalt with large areas of exposed and hardened dirt. Bicycles were everywhere with only the occasional Chinese-built black taxi. These taxis, I would learn, were generally reserved for foreigners and not local Chinese. I was with Lum Fook when I hailed a cab and the cabdriver initially would permit only me to enter his car. When I insisted that Lum Fook be allowed to enter, the driver became confused but eventually relented. I have no idea what happened to my minder. I remember thinking I had shaken him off. But there he was seated in my hotel lobby later that evening.

When the fullness of night arrived, the streets were often dark and punctuated only by the dimly lit storefronts. I remember many busy streets without street lighting and how strange it was to walk in such low visibility knowing that I was surrounded by people. I remember how vivid the sounds of chatter—and poultry—became when one could only make out what was a few meters in front. One noticeable oddity was taxicabs moving slowly through streets full of pedestrians and bicyclists without headlights on. Lum Fook said it was to preserve electricity.

We made it to his home, which was titled to my late grandfather, Lum Nin. Lum Fook was a dutiful relative and when there was a chance to leave China as the 1949 revolution approached, Lum Fook promised my grandfather, who had been in Canada since 1908, that he would ensure that the home would be safely guarded and kept within the family. I would later learn that with the Communist victory in the civil war all but confirmed, everyone else in the family left posthaste for Hong Kong or Macao. But Lum Fook stayed behind. I thought about the tenuousness of fate resting on one decision.

I was introduced to dozens of people who lived around the common courtyard. Some were convinced I was there in search of a bride and I would soon find myself in the company of someone’s daughter. I remember Lum Fook’s own daughter explaining to others that I was only visiting and not seeking marriage, but some daughters’ parents remained unconvinced.

Someone owned a small television set, apparently a gift delivered by a visiting relative from Hong Kong or from some place farther. The television was set high up in a small room for the watching family but faced a large window area that was fully opened to the courtyard. Seated all around the outside of this window in the courtyard were about a dozen people peering through the window to take in the television show. I remember how beautiful this scene was. Everyone was mesmerized by the spectacle of a lit-up television screen, never mind that Chinese broadcasts at the time consisted mostly of propagandistic newscasts and patriotic song and dance shows.

After dinner, I asked where the restroom was and Lum Fook and his family all laughed in mild embarrassment. I was told that it was located on the rooftop and they apologized for what I would see. The restroom, resembling a port-a-potty, also housed a biogas unit that turned organic waste into cooking fuel for the kitchen. Yes, some of the organic waste was visible to my eyes (which was the reason for the embarrassment), but I remember marveling at the toilet system and the way that it included a specially designed biogas stove. I often think about the eventual disappearance of such systems in favor of a less-sustainable system as China modernized.

After dinner, Lum Fook noted my interest in art and he led me to a closet that seemed not to have seen the light of day in some time. He took out some old books of famous Russian socialist realist painters and was surprised that their names were unfamiliar to me. Two of the books were basically picture books and printed in English. However, I had never heard of the artists. He kept insisting on how famous these artists were, and I remember how confused and even sad he seemed that I was so ignorant of these artists. At that moment, he confessed that he once wanted to be an artist and had studied at an official art academy. He took out numerous figure drawings, all done in the academic style. He showed me brush paintings of shrimp, peonies, and mountain scenes with groups of tiny figures. We talked about art and I tried to convey something of the state of modern and contemporary art as I knew it from a Canadian and American context. He took out more paintings, more abstract in nature. He told me that he paid a price for these paintings during the time of the Cultural Revolution. He did not elaborate except to convey to me a deep sense of pain at his rupture from the life of art. At that moment, I felt my own privilege, despite my own family’s history of hardship in Canada. I thought also about fate being tethered to a single frame of time and how Lum Fook’s love of art, abundantly palpable that it still seemed to be, and my own love of art ran parallel. This moment remains vivid to me in the most profound way.

The very next day, the final day of my first visit to China, I was awakened very early in the morning by recorded voices booming over loud speakers. and punctuated by patriotic music accompaniment. It was still dark but there was the first hint of sunlight. I parted the curtains in my room to take in the view of the Pearl River and the iron bridge again. I saw a sea of people on bicycles crossing the bridge, with half crossing in one direction and half the opposite direction. In that moment, I sensed something of the future of China.